White supremacist rally could be tipping point for tech's tolerance for hate speech

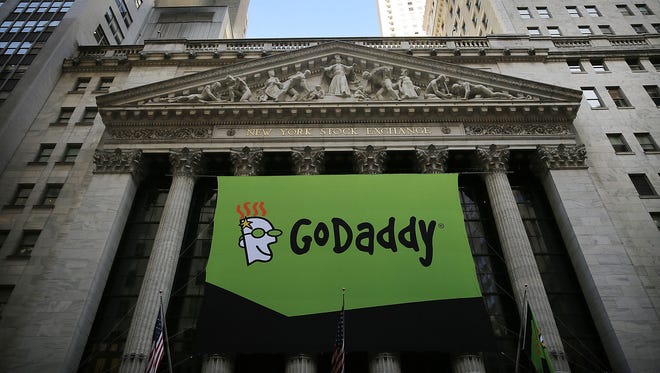

SAN FRANCISCO — A rise in domestic hate groups — whose vitriol spilled from online forums to the streets of Charlottesville during a violent weekend protest by white supremacists — is intensifying pressure on GoDaddy, Twitter, Google and others to put a lid on U.S. extremist sites.

Civil libertarians and religious leaders say the deadly Charlottesville protest on Saturday could be a tipping point for technology services to bow to consumer outrage and boot white nationalist and neo-Nazi sites that violate terms of service.

If this happens, it will be a change that's slow in coming. Many Internet providers and platforms include policies that allow them to drop customers and users for a variety of reasons, including incitement of violence and hate speech. But they also have cast themselves as forums for the free-wheeling debate that's been a hallmark of the Internet, a role that makes them loathe to police the content their users share.

The eviction of neo-Nazi website The Daily Stormer by GoDaddy and then Google from their domain servers comes after months of complaints to GoDaddy about the white supremacist site's content. In November The Daily Stormer published a list of more than 50 Twitter users who had expressed fear about the outcome of the 2016 election, urging its readers to “punish” them with a barrage of tweets that would drive them to suicide.

Late Sunday, GoDaddy said it was ditching the site after it published a story using sexist and obscene language to disparage Heather Heyer, the 32-year-old woman who was killed during a counter protest after the Charlottesville rally.

"In our determination, especially given the tragic events in Charlottesville, Dailystormer.com crossed the line and encouraged and promoted violence," GoDaddy spokeswoman Karen Tillman says.

"Given this latest (Daily Stormer) article comes on the immediate heels of a violent act, we believe this type of article could incite additional violence," Tillman says.

According to a Whois, which displays domain registration information, The Daily Stormer switched its domain host to Google Monday morning. Three hours later, Google said it violated its terms of service and removed it.

Google, which owns YouTube, also banned The Daily Stormer's YouTube account. The channel now only displays a message that says, "This account has been terminated due to multiple or severe violations of YouTube's policy prohibiting hate speech."

"Content on hate sites is up significantly because they were energized by the presidential campaign — it took Charlottesville to bring the public's attention to them," says Keegan Hankes, an analyst at Southern Poverty Law Center, a left-leaning group founded to combat racist organizations in the U.S.

"These guys are early adopters of technology and incredibly skilled at spreading their messages online," Hankes says.

The Daily Stormer derives its name from Der Stürmer, a newspaper that published Nazi propaganda. Other web services used by the site — which boasts a “Troll Army” of readers to target journalists and a Jewish woman running for a California congressional seat — were put under public pressure to cut ties with the site.

The Daily Stormer’s email provider, Zoho, said in a tweet it would no longer let the site use its services “in response to inquiries.”

Cloudflare, a network that provides performance and security services used by The Daily Stormer said

it is "aware of the concerns" and it finds content on some of these sites "repugnant" but did not say it would stop providing services to the site.

Crackdowns

Tech companies say they want to allow for the expression of different views while avoid being used as a tool for physical harm, a balance that's made for patchy responses to charges they harbor and enable abuse and violence.

They've often exerted stricter enforcement of terms of service after external pressure. Last year, Twitter purged several high-profile Twitter accounts connected to the alt right on the same day it said it was cracking down on hate speech. Among those banned was white nationalist Richard Spencer. A month later, Twitter reinstated his verified account, claiming the suspension was because he managed multiple accounts with overlapping uses. Spencer continues to maintain a verified account, sending updates during the protests in Charlottesville.

This year Twitter has taken several steps to curb abuse as CEO Jack Dorsey and other execs admitted harassment on the platform had gone too far. Its policy forbids conduct that “promote(s) violence against or directly attack or threaten other people on the basis of race, ethnicity, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, religious affiliation, age, disability, or disease.”

Earlier this month, YouTube said it was acting more quickly to remove videos with content tied to terrorism or extremism after companies started pulling ads they found attached to ISIS and other videos. The Google-owned company also said it would crack down on videos considered hate speech.

Facebook employed similar strategies for extremist propaganda, revealing in June it’s using algorithms to search for words, images or videos potentially tied to extremist content. Facebook's term of service does not allow for hate groups.

"Facebook does not allow hate speech or praise of terrorist acts or hate crimes, and we are actively removing any posts that glorify the horrendous act committed in Charlottesville," Facebook spokeswoman Ruchika Budhraja said.

Those behind hate groups, however, often straddle the line in what they say online to avoid violating terms of service and being booted.

The solution won't be easy, cautions Rabbi Abraham Cooper, associate dean of The Simon Wiesenthal Center. When stores displayed offensive products, they were removed; on the Internet, that is quite another thing, he says.

"We have a new-generation of extremists not driven by David Duke... but Richard Spencer and (Daily Stormer founder) Andrew Anglin," Cooper says. "Not all the blame is on the Internet, but the social media world should reflect the mores of the real world."

"I fear young people who don't understand history are being victimized by extremists at each end," Cooper says, referring the white nationalists and ISIS.