U-M’s Jim Harbaugh enjoys picking the minds of legends

ATLANTA — As the conversation spun around the circle, Jim Harbaugh’s eyes rapidly followed.

Sitting in a quiet open classroom setting deep inside Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson High School, he was enjoying a conversation he will remember for the rest of his life.

Though Harbaugh was at the school and in town for a satellite camp — one of dozens he’ll attend this month — this precious hour was one he wanted to continue. He’s had many unique experiences in his life, let alone the last 18 months, meeting the president, Supreme Court justices, his idol Willie Mays and every rapper within reach.

Yet this, with baseball legend Hank Aaron to his left and former U.S. ambassador/civil rights leader/Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young another seat down, was an hour soaking in history.

The topics? Everything under the Georgia sun.

Michigan football travelogue: Where's Jim Harbaugh today?

The trio were gathered along with a few other representatives as members of Legal Services Corp.’s Leaders Council.

One of their tasks: brainstorming ways to improve civil legal aid for those in need.

While that was a meaty part of the conversation early on — with Harbaugh making substantial suggestions — his morning memory was made with Young, 84, and Aaron, 82.

Winding through a wide range of topics, the Free Press observed as three famous faces each inquired about the others’ world and swapped stories.

Young recapped his impressive eight-year run as Atlanta mayor, re-energizing the city with downtown investment, bringing thousands of workers above the poverty line, drawing the Democratic National Convention and showing a passion for the city that continues.

He explained about leveraging investment and was a major advocate for landing the 1996 Olympics, determined to show the South had grown beyond its negative stereotypes of a few decades earlier, central to his life.

Even at his advanced age, Young remains an advocate for Atlanta and Georgia, explaining to Harbaugh the state’s unique HOPE college program, which offers free college tuition for high-achieving students.

He’s had many chapters in his life, from the civil rights struggle, when he ran the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, becoming Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s close ally, to being the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations in the 1970s, to becoming the mayor for much of the 1980s, and with a street named for him, remains an eminently respected voice in the city.

When Harbaugh asked him about the famous march in Selma, Ala., a spot Harbaugh visited last year when working a satellite camp in Prattville, Ala., Young tried not to rehash the past, instead focusing on the future, then tossed in some humor.

“We’re trying to get some jobs down there,” he said. “I don’t think the way employment is going now, I don’t think we’re going to be able to crowd more jobs into the cities. So I’m trying to get people to move back to the South.

“We say since we got air-conditioning and integration, it’s a whole lot better.”

Which cracked up the room.

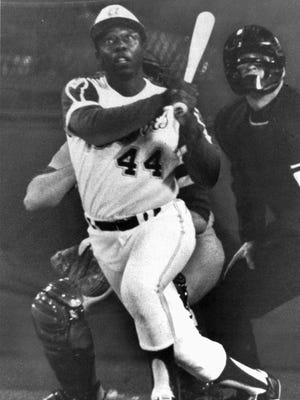

Aaron, baseball’s all-time RBI leader and second on the all-time home run list, told stories about baseball and how the game has changed — on the field and off it.

While crediting Willie Mays as the best all-around player he faced and Stan Musial as the best hitter — allowing that he rarely saw Ted Williams — the most interesting story began with identifying Sandy Koufax and Juan Marichal as the best pitchers he saw.

“And (Bob) Gibson. Koufax and Gibson were very different. When I say mean, he was just plain mean. He would throw at you in the on-deck circle. Back then nobody cared about getting hit. It was part of the game.”

Which led to Aaron reminding the difference between that game and this modern game.

“The meanest pitcher I faced was Stan Williams,” he said. “Stan was about 6-6 and about 230 and threw very hard. He hit me one day in Milwaukee. Wis. I had the bat on my shoulder, it was three balls and no strikes and (catcher) John Roseboro said, ‘Be careful, big boy.’ And he hit me with a three ball, no-strike count with a 92 m.p.h. fastball. I said, ‘I can’t get out of this game because if I do, the news is going to be spread around who’s chicken. They came by and gave me some smelling salts. I get to first base and remember Gil Hodges was still playing and (Williams) went to pick me off and hit me in the knee. Bop. Gil Hodges touched me like this and said, ‘Why don’t you go out and pinch his damn head off, big boy?’ I said, ‘Leave me alone, I’m not going to get beaned twice. The next time I might hit a home run off him.’ ”

The current generation may not react the same but their bottom line is much different as well.

“My first year in baseball we won the pennant and we got $10,000,” Aaron said. “I had a family. So I would walk to the ballpark every day to try to get my money. He said, it’s coming, it’s coming. So finally it did come so I got it and went to the bank and put my check there and they said, ‘Mr. Aaron, what do you want us to do with this $10,000. I said, I want you to count it all. I went home and I was staying in a little (place) and I pulled all the shades down and I spread it out. After I looked at it for awhile, I said ‘You’ve got to pay some bills.’ After that, I had $117 left.”

While Harbaugh didn’t have the extended history of Young and Aaron, one of his legendary connections came in his first full-time coaching job, hired in 2002 by the Oakland Raiders and colorful owner Al Davis.

“I was the low man on the totem pole, there was no lower man,” Harbaugh said of beginning after his 15 years playing in the NFL. “He was wonderful. I was getting paid a salary of $30,000 per year and I was working 120 hours per week. Mr. Davis said: ‘You know Jim, you really should be paying us for what we’re teaching ya.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, I should be paying you.’ I was definitely drawing the long straw. But the man had an incredible mind … He would just dazzle you with the way his mind worked.”

Harbaugh may have been the last outstanding coaching discovery in Davis’ long and rich NFL history, eventually revitalizing Stanford, coaching the San Francisco 49ers to the Super Bowl and now turning around Michigan.

“Then when I was leaving the Raiders to go to the University of San Diego, it was a very small school, they didn’t give scholarships out, I really wanted to be a head coach I had to tell Mr. Davis that I was leaving to coach at USD,” Harbaugh recalled, emulating Davis’ unique drawl. “Mr. Davis said, ‘Jim, I really thought you wanted to be a pro coach, that’s why I brought ya in here.’ I said, ‘Mr. Davis, I’ve studied you, I studied your career and you started as a college coach. I want to emulate your career.’

“He said, ‘Yeah I started as a college coach — at USC! Not USD!’”

As Harbaugh rose to leave, disappointed it had to end, he switched gears.

“It’s been an honor, a pleasure and a blessing to sit with you here,” he said to Aaron and Young, by now a room filling with reporters and others drawn in by the legends. “You got me fired up, I’ve got to go do my job, got to go coach somebody.”

Then he was off, headed to the football field, his unique morning parked away until his next unique experience.

Contact Mark Snyder: msnyder@freepress.com. Follow him on Twitter at @mark__snyder. Download our Wolverines Xtra app on iTunes and Android!