Two brothers, two petitions for clemency, two different outcomes

WASHINGTON — In the 1990s, Harold and Dewayne Damper were involved in a drug trafficking operation that brought cocaine from Southern California to Jefferson Davis County, Miss. — at the rate of about 1 kilo of cocaine a month, prosecutors said.

The two brothers, known as "Odie" and "Doogie," were indicted together, tried together, given the same sentence and, until recently, served their sentences at the same minimum-security prison.

When President Obama announced a clemency initiative to give drug dealers like them a second chance, both applied for presidential clemency.

Dewayne received a commutation and was released to a halfway house last week. Harold's case was denied. He's still in prison.

The Damper case illustrates a central challenge in the clemency initiative, as the Justice Department has tried to evaluate the record 32,551 commutation petitions it's received during the Obama presidency. Each case is reviewed separately and on its own merits, leading to complaints that the criteria are often applied inconsistently and subjectively.

"I've looked at a lot of cases and wondered, why this guy and not that guy? It's the process. When you have a process that is vertical and goes through seven layers of review, you’re going to get aberrational results," said Mark Osler, a law professor at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota and a leading advocate of changing the clemency system. "The problem is the process, not the president."

Those layers of review include staff attorneys and the heads of the Office of the Pardon Attorney, the Deputy Attorney General's Office and the White House Counsel's Office. Only then do the recommendations go to the president. The Constitution gives the president alone the power to "grant pardons and reprieves for offenses against the United States." Commutations are a lesser form of pardon that releases convicted criminals from prison but otherwise leaves the conviction intact.

The brothers appear to have been treated differently even before their petitions were filed.

Both sought the help of the Clemency Project 2014, an independent coalition of defense attorneys that agreed to take on clemency initiative cases for free. Dewayne received a free attorney. Harold did not and filed his petition himself.

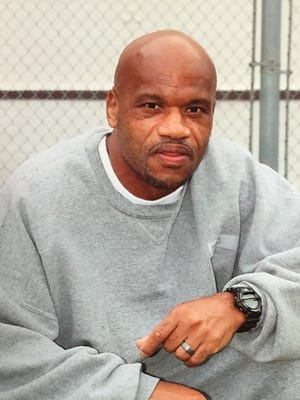

"I didn't get no feedback from them or nothing. I didn’t get looked at, really," Harold said in an interview from the low-security prison in Lompoc, Calif. "To me, it's the luck of the draw who gets a lawyer. That's all it is."

Read more:

Obama granted pardons by autopen. Could Trump grant them by tweet?

Obama's Iran pardons have unusual conditions

Obama promises more pardons, but can he do it?

Osler said the clemency process has inadvertently perpetuated injustices in the criminal justice system. "If you have a good lawyer, you're most likely to get a shorter sentence in the first place. And now with clemency, if you have a good lawyer for that, that helps you, too."

The Clemency Project would not discuss individual cases. Project Manager Cynthia Roseberry said each case is reviewed on its own merits.

"I will say this generally: Not only during this project but in my 20 years of practice, I've never found two identical defendants, not even in the same case," said Roseberry, a former federal public defender. "Each defendant has their own privacy issues and their own particular circumstances, regardless of being related to each other or not. So the lawyers would have looked at them independently."

Conditions for clemency

Under the clemency initiative, the president would consider releasing federal prisoners who:

• Are serving a sentence that would be substantially lower if convicted of the same crimes today.

• Were non-violent, low-level offenders without significant ties to gangs.

• Served at least 10 years of their sentence.

• Had no "significant" criminal history.

• Have a record of good conduct in prison.

• Have no history of violence.

"The clemency initiative boils down to two basic things: Would the person have a shorter sentence if they were sentenced today? And secondly, would they be a threat to public safety if they were released?" said Dena Iverson, a Justice Department spokeswoman. "These public safety factors often differentiate two cases that ostensibly look very similar."

The public safety test considers the inmate's offense, his or her criminal history conduct while in prison — which is not part of the public record, Iverson said.

Though they were convicted of the same crime, there were differences in their involvement. Harold was involved in the operation beginning in 1990. Dewayne was in a California prison serving time for a previous drug offense and didn't join until 1994. Prosecutors said both Harold and Dewayne supervised the operation, but Harold had a more significant role in the drug conspiracy.

A jury acquitted both Harold and Dewayne of the conspiracy charge and of the larger weights. Although Harold was charged with trafficking in 96 kilograms over eight years — and Dewayne of 39 kilos over three years — they were convicted only of possessing the 18.6 grams they sold to a confidential FBI informant in 1995.

"Basically, we got found not guilty of the big drug amount and the leadership role," Harold said. "We got our time for the thing we were found not guilty for. They couldn’t do that now."

A pre-sentence report, not normally public but obtained by USA TODAY, showed that the judge considered that leadership role in sentencing despite the objections of Harold's attorney. It also revealed that Harold has one juvenile assault conviction, for throwing an object at a vehicle when he was 12, injuring a baby inside. He served three months in a juvenile rehabilitation camp.

When the brothers were sentenced in Hattiesburg, Miss., in 1999, the judge noted that Dewayne had the more serious record. He had two prior felony drug convictions; Harold had one. "Although Mr. Harold Damper's record is less serious than Mr. Dewayne Damper's, it's still pretty serious," Judge Charles Pickering said, according to the transcript.

He gave them both the same mandatory minimum sentence: 30 years in prison and a $4,500 fine.

It's those mandatory minimum sentences Obama is trying to reverse through his clemency power.

"The framers gave the president this authority to remedy individual cases of injustice," Obama said in a Harvard Law Review article published last week. He said the clemency initiative was an effort "to look more systematically at how clemency could be used to address particularly unjust sentences in individual cases."

The emphasis on the word "individual" is in contrast to advocates of clemency-by-category, who want to see Obama grant mercy to broad categories of offenders, from low-level drug traffickers to undocumented immigrants. They cite President George Washington's mercy for the Whiskey Rebellion, Abraham Lincoln's forgiveness for Confederate soldiers or President Gerald Ford's amnesty for Vietnam-era draft dodgers.

Obama views the pardon power as a case-by-case determination, reserving the right to make judgments such as those in the Damper case.

"The way we got into this mess was to assume that people were identical and to sentence them in a cookie-cutter fashion," said Roseberry of the Clemency Project. "Everybody is singularly different."

Harold's petition was denied Jan. 5, 2016, and Department of Justice rules require him to wait one year to file again. Obama's term ends in less than two weeks, so his fate will probably be left to President-elect Donald Trump. Trump hasn't indicated what his clemency policy will be.

Harold, 49 and a grandfather, is scheduled to be released on Christmas 2024 with credit for good behavior.

"We're all really happy for Dewayne," said Harold's wife, Donalene, who dated Harold in high school and married him in prison in 2011 after Dewayne played the role of matchmaker. "We just want them both to come home."

Read more:

Obama grants clemency to inmate — but inmate refuses

Obama grants 98 more commutations, setting single-year clemency record